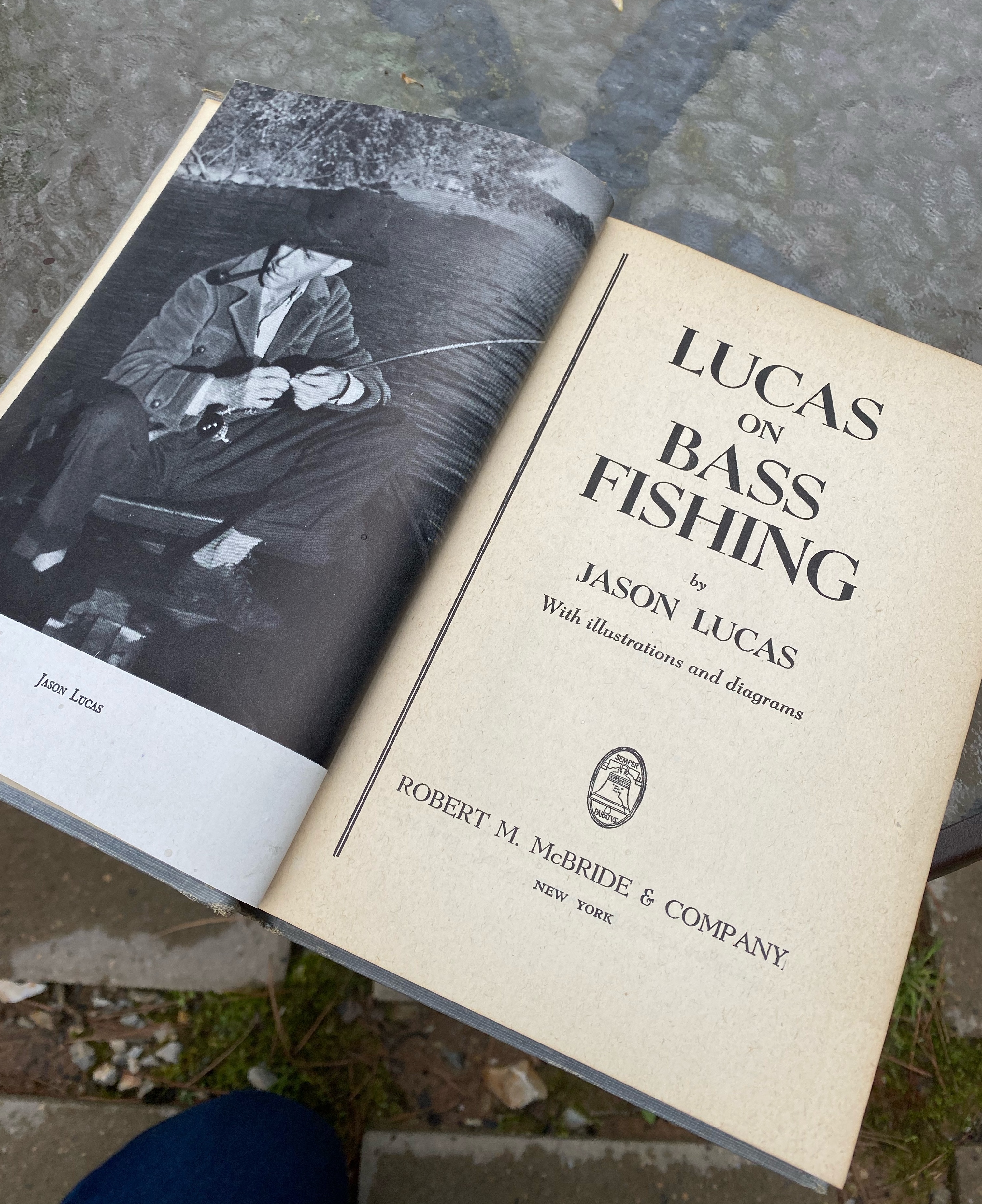

Jason Lucas

Jason Lucas — Born in Yorkshire, England in 1894, Lucas was instrumental in popularizing bass fishing through his writings for Sports Afield and later Sports Illustrated. Initially a fiction writer, Lucas wrote several western novels in the 1930s before he established himself as an authority on bass fishing at a time when trout were still considered the prized gamefish among anglers. His writings were based on experiences from spending countless days on the water. At one point, he claimed to have fished eight hours per day for 365 consecutive days. In 1947, he published Lucas on Bass Fishing, one of the first how-to books devoted to the pursuit of bass. It was later updated and reprinted twice, adding information about other freshwater species. In the book’s introduction, Ted Kesting, then the editorial director at Sports Afield, wrote, “When I first heard about a fisherman by the name of Jason Lucas, I put him down as another one of those piscatorial experts who are handier with conversation in a bar room than they are with a casting rod in a boat. … Then one day an associate of mine asked Lucas to write an article about bass. I read it and was amazed. This man really knew something about fishing.” Later, Kesting assigned Lucas a series of articles on his new angling techniques. The resulting reader response was overwhelmingly positive, and Lucas was then hired as the magazine’s angling editor, a position he held for more than 20 years.

Jason Lucas

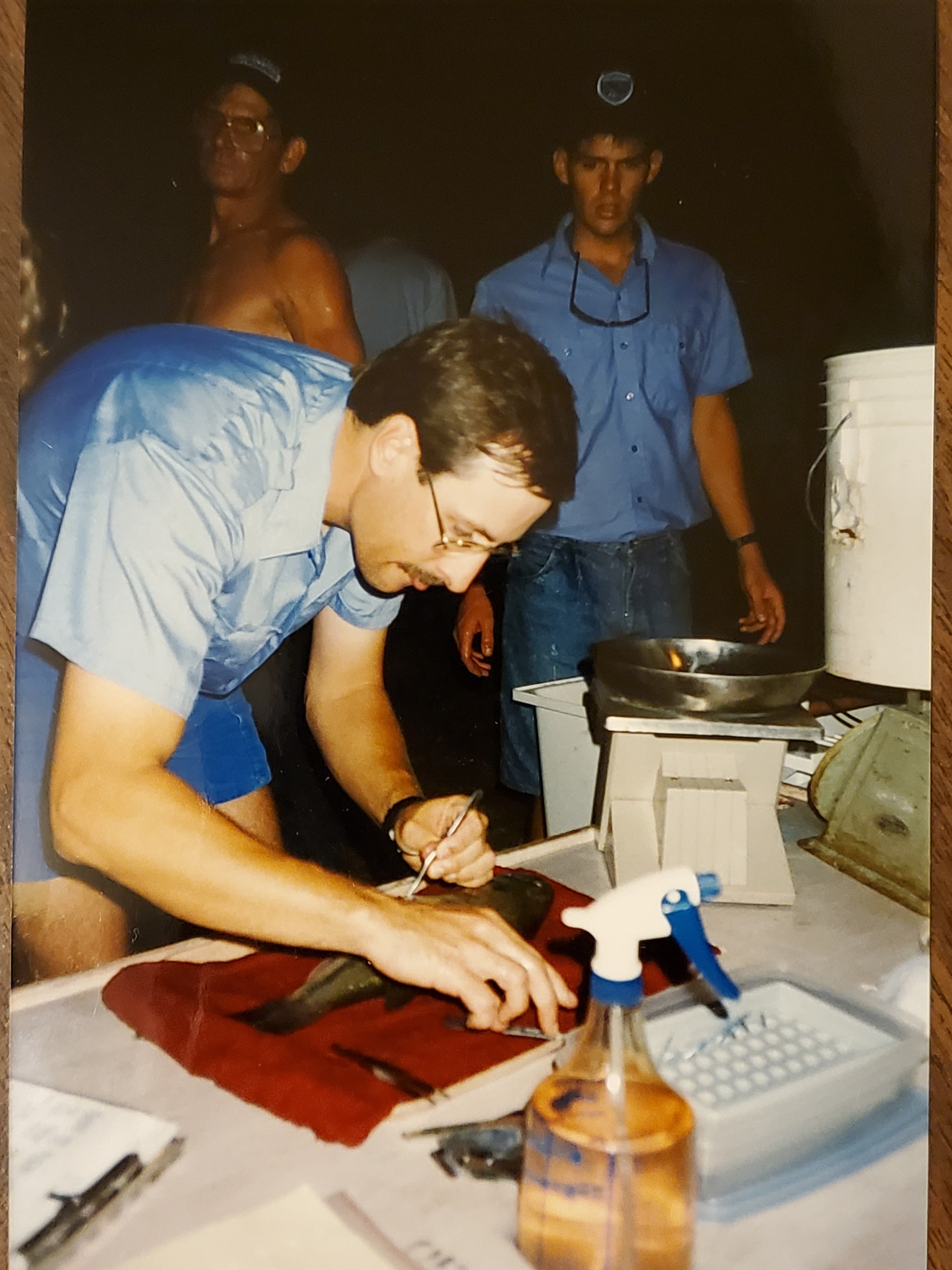

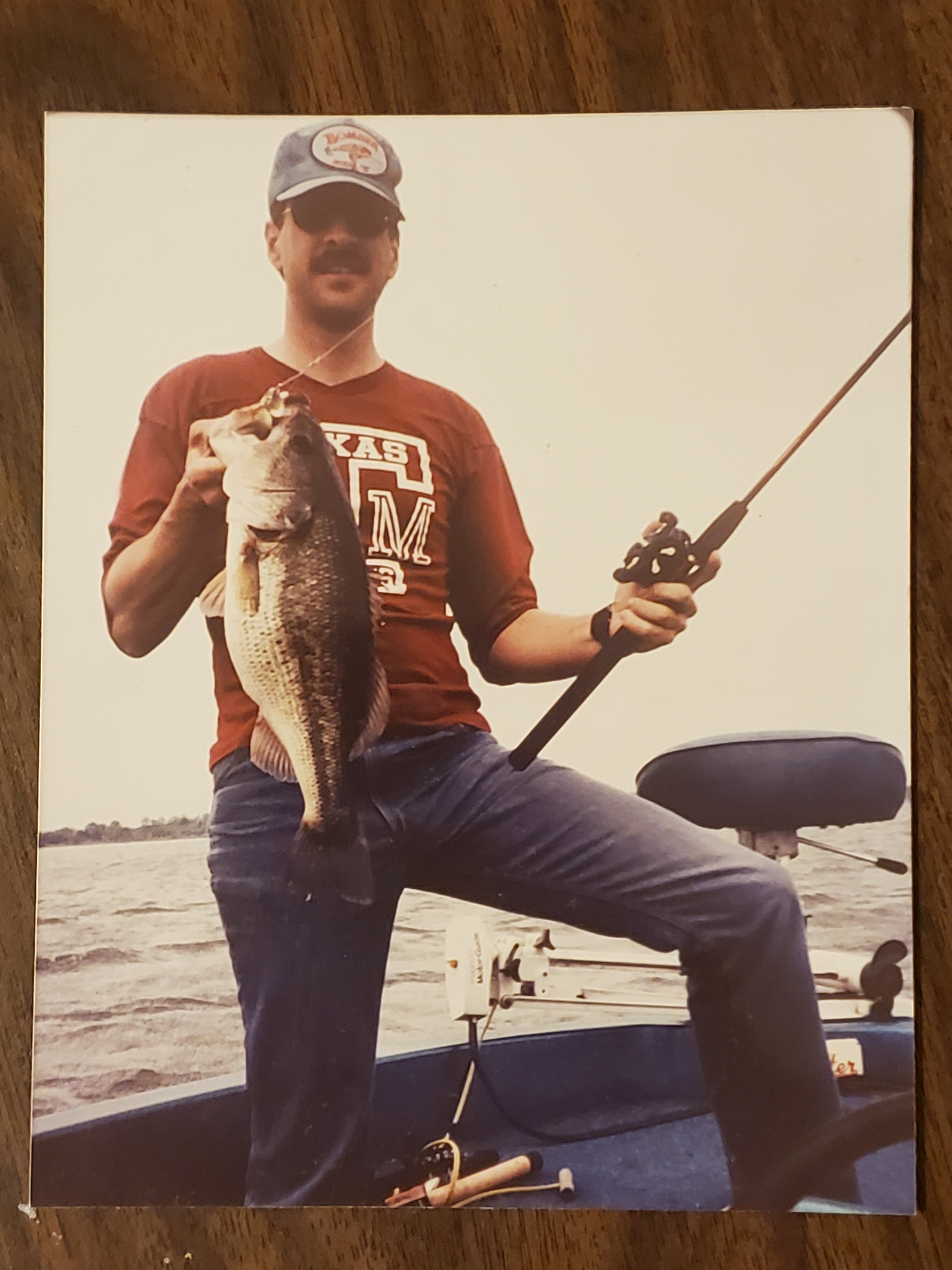

Gene Gilliland — Gene Gilliland, a nationally known fisheries biologist, was 12 years old when he was first introduced to fishing by family friend “Uncle” Ralph Buckingham. Uncle Ralph put a ZEBCO 33 in Gene’s hand and tied on a Johnson Silver Minnow with an Uncle Josh pork frog trailer – and they went bass fishing. That lit the fire that still burns today.

Curtis and Genie Gilliland supported their son’s fishing obsession and bought a jon boat. Gene and childhood friend Charlie Steed (deceased) taught each other to fish on local farm ponds and the pair soon stepped up to a small bass boat, fishing lakes all over North Texas. They were frequent visitors at Bomber Bait Company in their hometown of Gainesville, Texas, where founder Clarence “Turby” Turbeville kept them supplied with baits. They learned about bass fishing from BASSMASTER Magazine and by watching Bill Dance on TV. They joined B.A.S.S. and the Gainesville Bass Club, where experienced adult anglers like Ray Nichols and Tim Bullard became friends and mentors to the teenagers.

Gene’s life-changing moment in fishing wasn’t a big catch or a tournament win. It happened while Gene and Charlie were attending the 1972 BASSMASTER All-American Tournament weigh-in at Lake Eufaula, Oklahoma. They met B.A.S.S. founder Ray Scott who was promoting the revolutionary concept of releasing tournament bass alive. Scott showed them the tank used to hold bass prior to release. That tank and the catch-and-release concept ultimately changed tournament fishing and the mindset of bass anglers – and would influence Gene’s future in ways that he could never have dreamed.

Gene already had an interest in biology when high school science teacher Ronald Green told him about careers in fisheries. Gene interned that summer for the Texas Parks & Wildlife Department and got hooked on the science. He enrolled in the Fisheries Sciences program at Texas A&M and after completing his degree, his advisor, Dr. Richard Noble, encouraged him to pursue graduate studies. Gene landed at Oklahoma State University and earned a master’s degree.

Following graduate school, he was hired by the Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation (ODWC) at the Fishery Research Lab in Norman. Fisheries Chief Kim Erickson and supervisor Greg Summers gave him free rein to design and conduct bass research projects. Veteran biologist Jeff Boxrucker was always there for advice and counsel. Gene spent over a decade refining the agency’s Florida bass stocking protocols, was responsible for bringing smallmouth bass from Tennessee and stocking their offspring in Oklahoma reservoirs, helped develop ODWC’s Black Bass Management Plan, and coordinated aquatic vegetation introductions and habitat enhancement projects.

As tournament popularity grew, so did concerns about the impacts on bass populations. Gene became the liaison between ODWC and tournament organizations. In the early 1990’s he began research looking at fish dispersal from weigh-in locations. Alan McGuckin who went on to career in the fishing industry, was a University of Oklahoma graduate student and helped with that study. Gene and Alan shared a passion for the sport and became fast friends, a friendship that has lasted 30 years.

Realizing that bass club weigh-ins were less than optimal, in 1993 Gene and his technician Rick Horton created a “Weigh-in Kit” to help clubs run “fish-friendly” weigh-ins. A partnership with Falcon Rods and Gene Larew Lures funded distribution of kits to tackle shops who loaned the equipment, free of charge. Media coverage caught the attention of Al Mills, then B.A.S.S. Environmental Director, who invited Gene to speak at a conservation workshop. That speaking engagement began a long professional relationship with B.A.S.S., working with each successive Conservation Director (CD) – Bruce Shupp, Chris Horton and Noreen Clough (deceased).

From 1994 to 1999 Gene took tournament fish-care recommendations made by other researchers and tested them in controlled situations, developing a set of best practices. Studies and data compilations done by long-time colleague, friend, and later fishing buddy Dr. Hal Schramm were invaluable in developing the research. Gene and Rick’s backgrounds as tournament anglers proved advantageous in defining objectives and communicating with anglers, tournament organizers, and the public.

After seeing Gene’s research presentation at a conference in 2000, B.A.S.S. CD Bruce Shupp commissioned Gene and Hal to collaborate on Keeping Bass Alive, A Guidebook for Tournament Anglers and Organizers (KBA). That publication became the defining document on tournament fish care. It was distributed to tens of thousands of anglers, tournament organizations, and state agencies; has been quoted in countless print and website articles. Although the science has advanced since KBA was first published, the basic principles are still relevant and have been validated in more recent studies.

Gene has attended all but one BASSMASTER Classic since 1993 participating in conservation workshops and assisting with fish care. He wrote a column for B.A.S.S. Times for over 17 years about black bass research, management, and conservation issues. He also became a trusted source of information for outdoor writers across the country and was often invited to speak at angler workshops and professional conferences.

Gene’s body of work has been recognized by all levels of the American Fisheries Society for his scientific contributions and for his public outreach efforts. He was inducted into the Fisheries Management Hall of Excellence in 2014, one of the highest honors in the fisheries profession.

In 2013, Gene retired from ODWC after 32 years. At the urging of retiring B.A.S.S. CD Noreen Clough, Gene accepted the position as her replacement and holds it today. Gilliland is regarded as a voice for bass fishing on numerous national boards and councils where B.A.S.S. holds a seat. Gene helps guide the B.A.S.S. Conservation Agenda, provides content for the company website and social media platforms, works with the tournament staff ensuring the highest levels of fish care are followed, and acts as a mentor to the volunteer B.A.S.S. Nation state Conservation Directors, assisting with local and state issues. He has served on the board of directors of the Bass Fishing Hall of Fame since 2014.

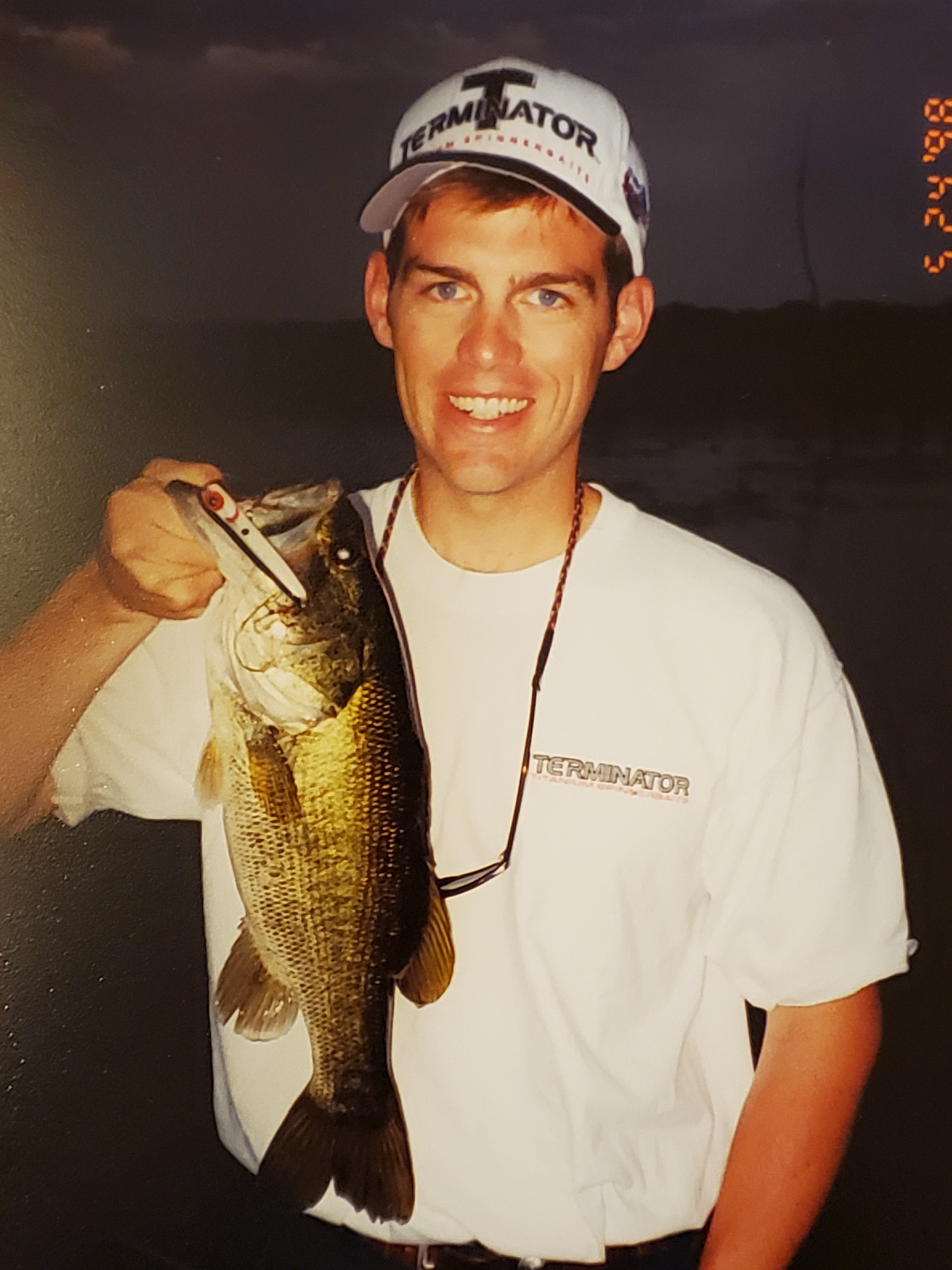

From that early relationship with Bomber Bait Company, Gene stayed connected with the fishing industry. He worked with the many companies that have called Oklahoma home (Falcon Rods, Zebco/Quantum, MotorGuide, Gene Larew, Lowrance, Hart, Terminator, Storm). In his current role with B.A.S.S., Gene has developed relationships with many other companies like AFTCO, Yamaha, Shimano, and Berkley that share a conservation ethic, and he is constantly recruiting other companies into the fold. He remains a champion for conservation of the resources that the sport and industry depend on.

Gene fishes more for fun these days, mostly with friend of 20+ years Steve Clay, whom he met through the North Oklahoma City Bassmasters, and with his wife of nearly 40 years, Pat, who has a growing passion for the sport. He still volunteers as a boat captain for the Oklahoma City Junior Bassmasters that he and Clay helped start in 2004 and will fish a club or Oklahoma B.A.S.S. Nation tournament now and then as schedules allow. He stays connected with fisheries management through professional societies, and with the broader bass tournament scene via his work, from websites, podcasts, and social media.

Gene Gilliland

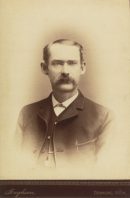

James Heddon (1845- 1911)— Credited with the invention of first wooden-body artificial lures in the 1890s, James Heddon, and his company James Heddon and Sons, produced the first commercially-successful lure called the ‘Dowagiac.’ The round tapered wooden body bait – especially designed for bass fishing, featured a three-tine hook at its rear end, with another three-time hook at its mid-point. From the book The Heddons and Their Bait, written by Donald D. Lyons. Heddon described the lure in his first product catalog as this – “In angling for bass (for which the “Dowagiac” is especially designed) or any other surface-feeding game fish, nothing is gained by making the bait to resemble any living thing. The Black Bass is primarily a fighter’ secondarily, a feeder; therefore that lure which excites his belligerency rather that his appetite is bet calculated to place in the creel. It is the commotion in the water and note the resemblance to frogs or minnows which attract the bass and excite the biting instinct. Imitation minnows, frogs, etc., may have tendency to catch the angler who does not know the nature and habits of the bass, but it is certain that these imitative qualities perform no part in provoking the ‘”strike.”

It can truly be said that all the way back in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, James Heddon knew bass. His passion for bass fishing is said to have started on the shore of Mill Pond in Dowagiac, Mich., where a sign at what is now ‘James Heddon Park’ commemorates his invention with these words – ‘It was near this spot in the late 1890’s that James Heddon sat whittling while waiting for a friend. When he got up to leave he tossed the small piece of wood into the water where it was immediately struck by a bass. That seemingly insignificant event led James Heddon to imagine and build a topwater lure which he called the ‘Dowagiac’. By the 1920’s James Heddon’s Sons was the world’s largest producer of quality fishing tackle.’ It’s a great story, and to this day, that is what it just may be.

Heddon’s innovations in using artificial lures to catch fish helped revolutionize bass fishing. Several of his creations remain popular today, including the Zara Spook, River Runt, Meadow Mouse and Lucky 13. James Heddon was born on August 28, 1845 and passed away at the age of 66 on December 7, 1911

James Heddon

Jay Yelas —Jay Yelas launched his professional tournament fishing career in 1989 and registered top-12 finishes in two of his first three events. During the first decade of the new millennium, he authored one of the greatest stretches of sustained excellence in the sport’s history, winning a Bassmaster Classic and three tour-level Angler of the Year (AOY) titles over the course of six seasons (2002-2007).

The native of Santa Barbara, Calif. knew he wanted to be a pro angler by the time he was old enough to obtain a driver’s license. After earning a degree in Resource Recreation Management from Oregon State University, he lived a vagabond existence for several years to achieve that goal. Over the next three decades, which included moves to Phoenix, Texas, and eventually, back to Oregon, he competed in more than 350 pro events and pocketed $2.5 million in tournament winnings with B.A.S.S. and FLW.

“I’ve always loved to bass-fish and it’s just a God-given talent,” he said during his early-2000s run of dominance. “I’m happiest when I’m using my gifts and creative talents.”

Unlike some of his contemporaries, Yelas has never been known as a guru of a single technique – versatility has long been his trademark. Even through the height of his success, his game evolved as new methods emerged from the West Coast. A lot of his initial success was achieved with spinnerbaits and jigs, but he was primarily employing swimbaits and dropshot rigs by the time of his third AOY crown.

His seminal year was 2002 when he won both the Classic at Alabama’s Lay Lake and the FLW Tour points championship. Fishing far up the Coosa River near the Logan Martin dam, he led the Classic from start to finish and took big-bass honors for each round, eventually outdistancing runner-up Aaron Martens by more than 6 pounds with a 45-13 total. The majority of his key fish in that event came from a 100-yard stretch of bank about 500 yards below the dam that was totally fruitless until the middle of each day, when a torrent of water was released from the dam for power-generation purposes.

Despite his pleasant, easy-going nature, he’s never hesitated to take a firm stand on issues that have arisen within the sport. He took a 13-year hiatus from B.A.S.S. competition after the ’06 Classic when he felt that the organization, then owned by ESPN, had shifted its media emphasis away from competition and toward angler antics that made for good TV. He used a “legends exemption” achieved via his Classic victory and AOY title to return to B.A.S.S.’ top circuit in 2019 after the organization had gone through two ownership changes since his departure.

He expresses his deep Christian faith at every opportunity and has long donated time and resources to charitable endeavors. He serves as the executive director for the C.A.S.T. for Kids Foundation, which aids special-needs children through numerous fishing events held annually throughout the nation.

Jay Yelas

Ron Lindner (1934 – 2020) – Ron Lindner — In 1970, about the time Ray Scott’s B.A.S.S. tournaments were starting to gain momentum, two brothers, both fishing guides in the Brainerd, Minnesota, area, decided to “test the waters” of outdoor television by filming a show teaching anglers how to catch fish on Big Sand Lake near Park Rapids, Minnesota.

With Al Lindner explaining and demonstrating the techniques on camera, the show was a success, and it led to hundreds more programs that have taught millions of people how to become better fishermen. As the on-air “talent,” Al was in the limelight, and he became one of the superstars of sportfishing in the Midwest and throughout the nation.

But Ron Lindner, Al’s older brother, deserved just as much credit for scripting, filming and directing that show and the numerous episodes that followed.

Together, the Lindner brothers went on to build a multimedia empire under the In-Fisherman brand, and they continue to influence sportfishing through their family-owned Lindner Media Productions.

In an effort to help anglers understand how to increase their fishing success, Ron Lindner came up with the formula, F+L+P=S (Fish + Location + Presentation = Success. That “algebra of angling” guided all of the Lindners’ educational platforms, beginning with the first In-Fisherman Magazine in 1974. In addition to the iconic magazine, the Lindners produced innumerable videos and DVDs, product sales videos and others.

At its zenith, In-Fisherman magazine had more than 300,000 subscribers, “In-Fisherman TV” was shown in 600,000 households, and the In-Fisherman Radio program was aired six times a week over 800 affiliate stations in 48 states.

Ron also co-wrote 10 books, and he wrote hundreds of published magazine articles and thousands of radio and TV scripts. He also devised a “fish response calendar” and a comprehensive system of classifying lakes, rivers and reservoirs designed to give anglers a shortcut to finding prevailing fishing patterns.

A professional guide, Ron also designed numerous articles of tackle and equipment, and he is an inventor with three patents and 30 unique designs to his credit. More than 70 million of his Lindy Rigs, which anchored the brothers’ successful Lindy Tackle Co., have been sold over the years.

After selling In-Fisherman in 1998, the Lindners turned their focus to Lindner Media Productions, which they founded along with sons James, Daniel and Bill. They continue to produce fishing educational videos under the names “Angling Edge” and “Fishing Edge,” and they produce commercial videos for many companies in the sportfishing industry.

In 2000, Lindner was selected as a member of the inaugural class of inductees into the Minnesota Fishing Hall of Fame. He and Al received the Hedley Donovan Award at the Minnesota Magazine and Publications Association annual awards program for their contributions to the magazine industry in 2002, and in 2007, the brothers were inducted into the Normark Hall of Fame. Ron Lindner was named a “Legendary Angler” by the Fresh Water Fishing Hall of Fame in Hayward, Wisconsin, in 1988, and he was inducted into that organization’s Hall of Fame in 2008.

After becoming a deeply committed Christian in 1978, Ron Lindner became passionate about sharing his faith, which he did through motivational speeches, magazine articles and radio interviews. He and Al founded or lent valuable support to several Christian charities. Their latest book, First Light on the Water, highlights the life lessons the Lindners learned on and off the water and explains how faith guides their lives.

- F+L+P = Success

Ron Lindner

Bryan Kerchal – (1971-1994) In July of 1994, 23 year-old angler Bryan Kerchal lived the dream of hundreds of thousands of weekend anglers by beating a star-packed field of anglers to claim the title at the 24th Bassmaster Classic. In doing so, he also became the first, and to date only, fisherman to win as a B.A.S.S. Nation qualifier, as well as the first northeastern angler to claim the coveted crown and the $50,000 top prize.

Kerchal may have attained fishing immortality while still exceptionally young, but the path to his Hall of Fame achievements was anything but easy. He was raised in Newtown, Connecticut, and after graduating from Newton High with the Class if 1989, he briefly attended Massachusetts’ Salem State University, where he spent more time poring over Bassmaster Magazine than his textbooks. He left school and took a part-time job as a cook at the Ground Round restaurant, which left time try to figure out his life’s work, while also pursuing his passion for bass fishing.

He’d been introduced to the sport through a neighbor and was self-taught until he joined the Housatonic Valley Bassmasters club. Through that B.A.S.S.-affiliated club, he qualified for the state championship tournament and made the 12-man Connecticut team, then qualified for the B.A.S.S. Nation Championship. His performance as the top Eastern Division angler there earned him a berth in the 1993 Bassmaster Classic on Alabama’s Logan Martin Lake. At the 1993 Classic he finished dead last, but there was stout company and no shame at the bottom of the leaderboard, as four-time Classic champ Rick Clunn beat him by less than a pound.

Defying incredible odds and the same daunting qualification path, Kerchal returned to the Bassmaster Classic as a B.A.S.S. Nation qualifier in 1994, making him the first to defend a B.A.S.S. Nation title and qualify for the Classic, as an amateur, twice. He’d fished six B.A.S.S. Invitationals that season, but the B.A.S.S. Nation was once again his route to the world championship. This time around, the results were quite different.

Kerchal suffered through a tough practice period at North Carolina’s High Rock Lake, and while many pundits predicted that the summertime conditions would allow Hall of Famer David Fritts to repeat his 1993 win using offshore tactics, heavy rain prior to the event raised and muddied the water. That made flipping to the lake’s many boat docks a more viable tactic. He’d found a red shad Culprit ribbontail worm floating in the lake during practice, and having little to lose he decided that would be as good a lure as any. Pitching that Texas-rigged worm with a 3/16 ounce bullet weight and a 2/0 Gamakatsu hook to three sets of docks in Second Creek, Kerchal weighed in three consecutive limits – the only angler to do so — that totaled 36 pounds 7 ounces. He ended Day One in fourth place and took the lead on Day Two. Veteran flipper Tommy Biffle caught 18-14 on the final day of competition to make a run for the title, but ultimately fell 3 ounces short of Kerchal’s catch.

Each time he caught a legal fish, Kerchal took out a small green whistle shaped like a bass and expressed his satisfaction through music. The fish whistle became a symbol of his excellence and his enthusiasm and has been picked up on by future B.A.S.S. Nation qualifiers, including 2017 B.A.S.S. Angler of the Year Brandon Palaniuk, who carried one while he fished as a B.A.S.S. Nation qualifier at the 2011 Classic.

“Most of the field had 10, 15, 20 years more experience than Bryan did,” Rick Clunn told the Charlotte Observer after Kerchal’s win. “He didn’t have nearly the knowledge that the rest of the field had. But I’ll trade all the knowledge in the world for enthusiasm and belief in you. As you get older in this sport, technology takes over. For a lot of fishermen, it steals the passion out of what they do. But mentally, all young people tend to have this belief in the impossible.”

Tragically, Kerchal did not get a chance to defend his title on High Rock Lake in 1995 or to fulfill his destiny. Less than five months after his history-making victory, he and 14 other died when American Eagle Flight 3379 crashed. He’d been making an appearance for one of the sponsors who’d seized upon his success and enthusiasm and partnered with him. At the 1995 Classic, a bassboat was driven around the arena with his trophy in it.

He was survived by his parents Ray and Ronnie Kerchal; a sister, Deana Kerchal; and longtime girlfriend Suzanne Dignon.

The B.A.S.S. Nation championship trophy was subsequently renamed the Bryan Kerchal Memorial Trophy.